|

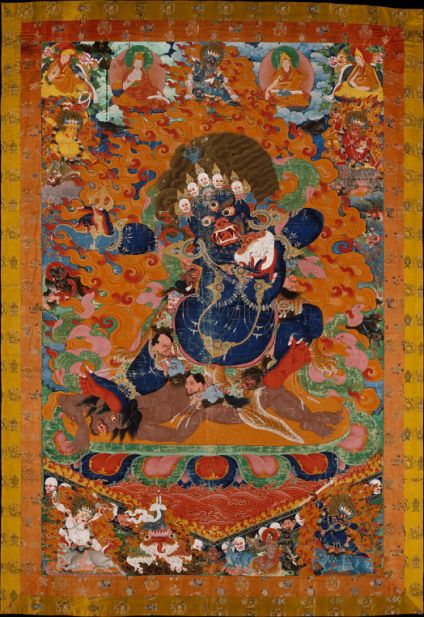

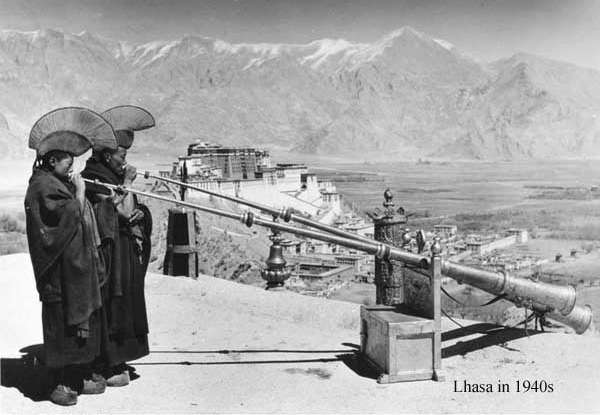

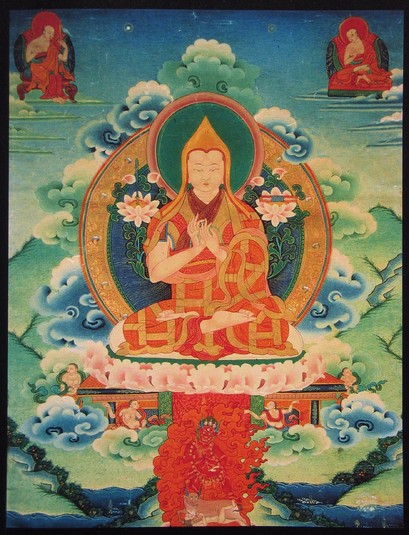

20. COMPLEXITIES OF BUDDHISM

What are your views on Buddhism? More specifically, the controversy about the Zen exponent D. T. Suzuki. In a wider context, Westerners are often puzzled at the very different traditions within Buddhism, to some extent perhaps explained by geographical factors. Buddhism started with a relatively simple, straightforward teaching, but eventually acquired an extensive array of gods, bodhisattvas, and Buddhas that can prove bewildering. How do you approach these matters? The factor of Tibet now seems to be significant in contemporary commentaries. Do you have a perspective in that subject?

20.1 Necessity for Detailed Study

My introduction to this religion occurred in 1965, when I visited the Buddhist Society of London. However, I did not commence a detailed study until the early 1970s, when I began to borrow books on Buddhism from Downing College Library in Cambridge. The Mahayana traditions were my favoured subject at that period. One task was to understand how the various sects and teachings had spread from India to Central Asia, Tibet, China, Japan, and yet other countries. The diversity of teaching, ethnic complexities, and the time-scale of many centuries, comprised a challenging field of investigation.

I discovered that many Western enthusiasts of Buddhism did not apply themselves to any detailed study of this religious phenomenon. They expected to get "enlightenment" by adopting the practice of meditation. There were many disappointments. The practitioners often opted to follow a particular tradition, usually Zen (associated with China and Japan) or Vajrayana (associated with Tibet). I did sample both of those traditions, but without becoming a partisan (Pointed Observations, 2005, pp. 43-5).

What interested me was the Buddhist phenomenon as a whole, and from a historical and philosophical standpoint, not from any sectarian one. How many times did I find Zen elevated above all other religions and philosophies? There were numerous instances of that approach available in popular literature; I developed an allergy accordingly. I became aware that specialist scholarship was probing Zen (Chan) in a more analytical spirit than generally known.

|

l to r: Daisetz T. Suzuki, Hu Shih |

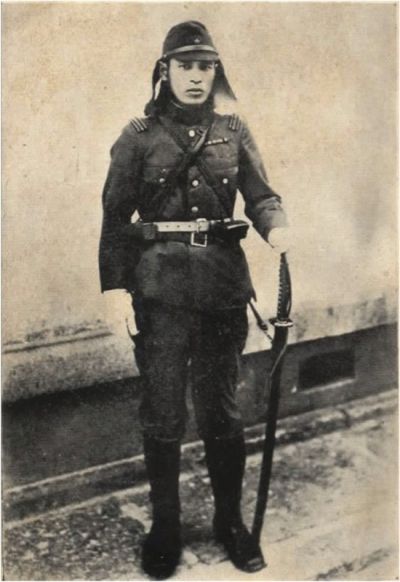

I returned to these matters in the 1980s at CUL (Cambridge University Library). I was able to track ongoing books like Professor Bernard Faure’s highly rated The Rhetoric of Immediacy: A Cultural Critique of Chan/Zen Buddhism (1991). A version of Zen was included in my Some Philosophical Critiques and Appraisals (2004), pp. 103-122. Here I incorporated a topic marginalised for many years prior to the 1990s, namely the debate between the Japanese savant D. T. Suzuki and the Chinese scholar Hu Shih. Both of these men were University Professors; their respective worldviews were conflicting.

A controversy now centres upon D. T. Suzuki, a Zen exponent criticised in relation to Japanese nationalism of the late Meiji era and the early twentieth century. The full argument has some strong extensions. There was a general tendency amongst Japanese Zen Buddhists, of the early twentieth century, to adopt nationalist attitudes of militarism, inspired by imperialist agendas. This discrepant trend was forgotten and ignored in the subsequent phase of Western enthusiasm for Zen. The compromised situation of Zen "enlightenment" invites due scepticism.

20.2 D. T. Suzuki, Zen, and Japanese Nationalism

Daisetz Teitaro Suzuki (1870-1966) became widely regarded in the West as the major expositor of Zen Buddhism. Some commentators state that he achieved enlightenment. He became a Professor of Buddhist philosophy at Otani University in Kyoto from 1921, and later a visiting Professor at Columbia University during 1952-7. His output should not be underestimated. He could speak seven languages and wrote many books. He contributed such influential works as Essays in Zen Buddhism (3 vols, 1927-34) and Zen and Japanese Culture (first edn 1938; second edn 1959). Another major book was his Studies in the Lankavatara Sutra (1932). Perhaps more widely read were his Manual of Zen Buddhism (1934), Living by Zen (1949), and The Zen Doctrine of No-Mind (1949).

.jpg)

D. T. Suzuki

|

The reputation of Suzuki for enlightenment derived from his early years. While studying at Tokyo University as a young man, he took up the practice of Zen at weekends, and during vacations, with the Rinzai Zen priest Soyen Shaku (1859-1919). This occurred at a monastery of Engakuji Zen Temple in Kamakura. Suzuki did not become an ordained monk, instead remaining a layman. His fabled enlightenment in 1896 is associated with the practice of koan, enigmatic phrases later becoming popular in America. Suzuki married an American Theosophist in 1911. Conservative Japanese Zen practitioners regard him as a populariser of Zen.

Suzuki’s version of Zen was innovative and apologist, following a Buddhist trend occurring in the Meiji era (1868-1912). His version of bushido, the cult of the sword, is very easy to criticise. Suzuki was the son of an army doctor, and the descendant of a samurai family. I questioned the status of enlightenment (satori) credited to Professor Suzuki by Western partisans of Zen (Shepherd, Minds and Sociocultures Vol. One, 1995, p.187 note 177). Descriptions of satori are often vague, making this experience easy to claim by persons far less accomplished than Suzuki. To his credit, the Japanese savant is reported to have been unimpressed by the Beatniks Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg; the occasion was a meeting they gained with him in New York in 1958. Suzuki apparently discerned the alcoholic problem of Kerouac. The Beat innovators believed they understood Zen; others were in strong doubt of their orientation.

After his Zen phase at Engakuji Temple, in 1897 Suzuki moved to America, where he remained until 1908. In later years, many Westerners came to regard him as a Zen teacher. However, he rejected that role, instead adopting the career of a writer and lecturer. In 1949, Suzuki said to one Western enquirer: "I am a talker not a teacher." His own report, of his 1896 satori at Engakuji, claimed the "real state of samadhi" in ceasing to be conscious of the Mu koan prescribed by his mentor Soyen Shaku. According to Suzuki, this experience enabled satori or enlightenment. The satori was endorsed by "a series of checking questions" in a formal interview with Shaku (Richard M. Jaffe, introduction, Selected Works of D. T. Suzuki Vol. 1, University of California Press, 2014, p. xxii). Both of these "enlightened" entities were sponsors of the Japanese war effort.

Suzuki has been accused of Zen nationalism. This theme is expressed by such scholars as Professor Robert H. Sharf. Zen nationalism involved a disconcerting factor generally ignored in the West during the lifetime of Suzuki:

It was no coincidence that the notion of Zen as the foundation for Japanese moral, aesthetic, and spiritual superiority emerged full force in the 1930s, just as the Japanese were preparing for imperial expansion in East and Southeast Asia. (Sharf, Whose Zen: Zen Nationalism Revisited, 1995)

Suzuki is here viewed in terms of presenting the Japanese Zen experience as both unique and universal. The deducible claim of some exponents like Suzuki was: "Zen is truth itself, allowing those with Zen insight to claim a privileged perspective on all the great religious faiths" (Sharf 1995:46). Zen uniqueness was introduced to the West "through the activities of an elite circle of internationally minded Japanese intellectuals and globe--trotting Zen priests, whose missionary zeal was often second only to their vexed fascination with Western culture" (Sharf, The Zen of Japanese Nationalism, 1993).

Sharf observes that Japanese military victories, including defeat of the Chinese in 1895, influenced a national tendency to view Japanese accomplishments with reference to bushido, the way of the warrior. "The fact that the term bushido itself is rarely attested in pre-Meiji literature did not discourage Japanese intellectuals and propagandists from using the concept to explicate and celebrate the cultural and spiritual superiority of the Japanese" (Sharf, Japanese Nationalism, linked above). A work by Nitobe Inazo entitled Bushido: The Soul of Japan, was published in English in 1900. This was the tip of the iceberg. "A generation of unsuspecting Europeans and Americans were subjected to Meiji caricatures of the lofty spirituality, the selflessness, and the refined aesthetic sensibilities of the Japanese race" (ibid).

.jpg)

Soyen Shaku

|

The first English language books on Zen emphasised a close relationship between Zen and the fashionable "way of the samurai." The first of these books was published in 1906, namely Sermons of a Buddhist Abbot by Soyen Shaku (1860-1919), a priest of Rinzai Zen who was the abbot of temples at Kamakura. He was also a teacher of Suzuki. Shaku included, in his published sermons, a brief defence of Japanese military aggression in Manchuria. The priest asserted: "War is not necessarily horrible, provided that it is fought for a just and honourable cause" (cited in Sharf, Japanese Nationalism). The nationalists viewed military aggression as honourable, in the cause of the divine Emperor. The Zen abbot glossed war with the statement: "Many material human bodies may be destroyed, many hearts may be broken, but from a broader point of view these sacrifices are so many phoenixes consumed in the sacred fire of spirituality" (cited in Sharf, art. cit.).

Soyen Shaku was keen to depict Westerners as being generally unsuited to Eastern mysticism. Large numbers of the aliens became converts to Zen and samurai lore. Many years later, some Westerners were keen to pay high prices for lethal Japanese swords, which gained a repute as being warrior talismans of a virtually transcendent category.

Soyen Shaku served as a chaplain to the Japanese army during the Russo-Japanese war of 1904-5. In 1904, the pacifist Leo Tolstoy (1828-1910) wrote to Shaku, requesting the abbot to join him in denouncing the war. Soyen Shaku refused, demonstrating a nationalist spirit. After that war, Shaku attributed the victory of Japan to the samurai code (Wikipedia Soyen Shaku, accessed 12/01/2019).

The second Zen book in English was Religion of the Samurai: A Study of Zen Philosophy and Discipline in China and Japan (1913). The author here was the Soto Zen priest Nukariya Kaiten (1867-1934), a university professor and a friend of Suzuki. One message in his book is that only in Japan was Buddhism still alive; the author promotes the idea that pure Zen could only be found in Japan. Moreover, "Zen is an ideal doctrine for a newly emergent martial Japan" (Sharf, Japanese Nationalism). Nukariya Kaiten stated: "It is Zen that modern Japan, especially after the Russo-Japanese War, has acknowledged as an ideal doctrine for her rising generation" (cited in Sharf 1993). Kaiten "argues that the spirit and ethic of Zen is essentially identical with that of the samurai" (Sharf 1995). Late Meiji era Zen apologists were keen on bushido and national spirit, an ideology blending easily with themes of imperial conquest and unconditional obedience to the Emperor.

Suzuki furthered the connection of Zen with bushido. "The notion that Zen is somehow related to Japanese culture in general, and bushido in particular, is familiar to Western students of Zen through the writings of D. T. Suzuki" (Sharf 1993). Suzuki remained a middle class Zen layman. Much of the writing about his life is "hagiographical in nature." Sharf further describes Suzuki as "a product of Meiji New Buddhism," meaning the reaction to government opposition and loss of income and land for Buddhist temples. The defensive partisans "readily admitted to the corruption, decay and petty sectarian rivalries that characterised the late Tokugawa Buddhist establishment." The new Buddhists of the late Meiji era "actively appropriated the ideological agenda of government propagandists.... They became willing accomplices in the promulgation of kokutai (national polity) ideology - the attempt to render Japan a culturally homogenous and spiritually evolved nation politically unified under the divine rule of the emperor" (Sharf 1993).

Despite the popular accolades gained by Suzuki in the West, Paul Demieville, "perhaps the greatest scholar of East Asian Buddhism of his day, decried the manner in which Suzuki attempted to embrace the whole of Japanese culture under the banner of Zen" (Sharf 1993).

Various critiques of Suzuki emerged in subsequent years. A strong issue is that of his alleged support for Japanese military aggression in Asia, including the Pacific War dating to 1937-1945. One of his emphases was "the sword that kills and the sword that gives life." Some have seen in such phrases "at the very least tacit support for Japanese militarism and expansionism in Asia" (Richard M. Jaffe, introduction, Selected Works of D. T. Suzuki Vol. 1, University of California Press, 2014, p. xvii). Suzuki definitely supported the earlier Russo--Japanese war and the colonisation of Korea. Japan annexed Korea in 1910, exploiting natural resources and cheap labour. The invaders forced Koreans to adopt the language and religion of Japan (primarily Shinto).

In 1904, Suzuki invoked Buddhism in his attempt "to convince Japanese youth to die willingly for their country." This was eight years after his "enlightenment." Satori decoded to warcry. In the Russo-Japanese war, 47,000 young Japanese men lost their lives in the death programme advocated by Suzuki, Soyen Shaku, and many other zealous Buddhist exponents. Subsequent articles of Suzuki, publshed during the Second World War, have also gained criticism. See Brian Victoria, "Zen as a Cult of Death in the Wartime Writings of D.T. Suzuki," The Asia-Pacific Journal (2013). The accusation is here lodged that Suzuki weaponised Zen, "turning Zen into nothing less than a cult of death."

In 1941, certain writings of Suzuki on Zen and bushido, appeared in Japanese military journals. This gesture of the author cannot be considered a gesture of pristine Buddhist pacifism. However, those writings of 1941 do not employ themes like "Japanese spirit" (yamato damashii), dying for the imperial cause, or State Shinto, concepts common in the output of other Japanese intellectuals of that era (Jaffe 2014:xviii). Suzuki's own agenda wished "to displace the increasing emphasis on Shinto as the foundation of Japanese life" (ibid:xvii).

The partisan Jaffe interpretation is described in terms of being "calculated to neutralise the criticisms that, since the 1990s, have destabilised his [Suzuki's] heroic image as a custodian of Asian tradition." Quote from George Lazopoulos, Zen Again: Reconsidering D. T. Suzuki (2015).

A defensive version of the contested situation is: "Like many Japanese intellectuals of his generation, Suzuki passively accepted Japanese imperial expansion and the increasingly military aggression against China in the 1930s, although Suzuki did later admit his guilt for his failure to be more outspoken" (Jaffe 2014:xvii). On several occasions during the late 1930s, and 1940s, he wrote (in private letters) that the war in Asia, and against the Allies, "would cause great harm to Japan" (ibid:xviii). In a letter of 1941, Suzuki commented: "This war is certain to take us to the brink of destruction - indeed we can say that we are already there" (ibid). By that time, Suzuki could evidently foresee the backlash from America.

.jpg)

The photograph on book cover shows Japanese monks at the Echizen Nagahira Temple performing military drill, 1930s

|

An American scholar of Zen has contributed the significant book Zen at War (1997; second edn, 2006), and also Zen War Stories (2003). Professor Brian (Daizen) Victoria reveals that Zen Buddhist traditions supported the aggressive political and military disposition of Japan during the first half of the twentieth century, and even afterwards. Almost all the Japanese Buddhist temples strongly supported Japanese militarism. A basic belief discernible is that war was necessary to implement dharma (Buddhist religion) in Asia. This disconcerting development was criticised by Chinese Buddhists.

The significant output of Brian Victoria "revealed that many leading Zen masters and scholars, some of whom became well known in the West in the postwar era, had been vehement if not fanatical supporters of Japanese militarism" (Victoria, Zen as a Cult of Death, 2013, article linked above). In response to these revelations, "a number of branches of the Zen school, including the Myoshinji branch of the Rinzai Zen sect, acknowledged their war responsibility" (ibid). This apology appeared in 2001, over half a century after the heavy casualty Pacific War ended in 1945.

Victoria has shown that Zen theory strongly influenced the Japanese military. A prominent example was Lt. Colonel Sugimoto Goro (1900-1937), who died in battle in China, hit by a grenade fragment. His famous posthumous book Taigi (Great Duty) was popular amongst young Japanese officers. He wrote: "Through my practice of Zen I am able to get rid of my self. In facilitating the accomplishment of this, Zen becomes, as it is, the true spirit of the imperial military." Goro described his role in terms of "soldier Zen." His death was honoured by Zen communities, who regarded him as a surpassing and god-like entity. Goro is well known for a nationalist theme of unity between the Japanese Emperor and his subjects:

The reason that Zen is necessary for soldiers is that all Japanese, especially soldiers, must live in the spirit of the unity of the sovereign and subjects, eliminating their ego and getting rid of their self. It is exactly the awakening to the nothingness (mu) of Zen that is the fundamental spirit of the unity of sovereign and subjects.

Goro was treated as a national hero by his teacher Yamazaki Ekiju, leader of Rinzai Zen. Ekiju was a fervent nationalist who celebrated the Emperor. Japanese wartime Zen leaders interpreted a Buddhist doctrine of the non-existence of self in an improvised manner, meaning complete willingness to die in the service of Emperor and state. This was definitely not the original meaning of such concepts (Victoria, "A Buddhological Critique of Soldier-Zen in Wartime Japan," in M. Jerryson and M. Juergensmeyer, eds., Buddhist Warfare (Oxford University Press, 2010). The war against China was justified by soldier Zen. Obedience to the Emperor was first and foremost.

The crux of this situation is: "Institutional Buddhist leaders were united as one in their fervent promotion of the war effort" (Victoria, Zen War Stories, New York: Routledge 2003, p. 226). Rinzai leader Yamazaki Ekiju wrote; "The faith of the Japanese people is a faith that should be centred on His Imperial Majesty, the Emperor" (ibid). The Zen communities were monarchist at this period.

Lt. Colonel Sugimoto Goro

|

The Zen soldier Sugimoto Goro affirmed that, amongst Buddhists, only the Zen movement had enshrined the Emperor in image formats featuring Amitabha Buddha. A wartime emphasis of influential layman D. T. Suzuki is also revealing: most of Japan's problems could be solved instantly "if the warrior spirit, in its purity, were to be imbibed by all classes in Japan" (Victoria 2003:202).

Zen exponents of that era employed themes of no-self and non-duality "to legitimate Japanese militarism and indoctrinate soldiers with an ideology of self-sacrifice." This tendency jettisoned the essential Buddhist precept of ahimsa or non-violence. A loophole for this dismissal was the nondual doctrine of emptiness (shunyata). The reported exhortation of a seventeenth century Zen teacher to a warrior patron reads: "The uplifted sword has no will of its own, it is all of emptiness.... The man who is about to be struck down is also of emptiness, and so is the one who wields the sword." This relativist message was tailor-made for samurai actions of killing. Zen was accordingly often criticised by other Buddhist traditions for antinomian dismissal of monastic ethical precepts (James L. Ford, The Divine Quest, East and West, State University of New York Press, 2016, p. 297).

In 1941, the Soto Zen leader Omori Zenkai (d.1947) was a strong supporter of Japanese militarism. He wrote: "It is in killing the idea of the small self that we are reborn as a true citizen of Japan" (Victoria, Zen War Stories, p. 116). A serious confusion is evident. Soldier Zen, and the Japanese army in general, was not killing the small self but instead victim bodies that became corpses.

Brian Victoria has revealed how a group of Zen-inspired terrorists assassinated two major political figures in 1932. An allied group killed the Prime Minister Tsuyoshi Inukai, with catastrophic effects for Japanese democracy. The terrorist leader was Inoue Nissho (d.1967), an army spy who resorted to Zen meditation in 1921. He reputedly gained “enlightenment” under the famous Rinzai Zen master Yamamoto Gempo. Nissho subsequently indoctrinated young patriots who became his accomplices in terrorism. These nationalist assassins were sentenced to life imprisonment, but released in 1940. Nissho then became an adviser to the Prime Minister Konoe Fumimaro during World War II.

To train his terrorist band, Inoue Nissho employed traditional Zen methods, including meditation and koan. He at first only envisaged legal political activism. By 1930, he resolved upon killing, drawing inspiration from the koan collection called Mumonkan. One of his group later gave the explanation: “We sought to extinguish Self itself.” In his own court testimony, Nissho disclosed: “I was primarily guided by [Mahayana] Buddhist thought in what I did.” He also stated: “I transcend reason and act completely upon intuition” (quotes from Victoria, Zen Terror). The extreme confusions here resulting from putative Zen enlightenment, and the use of koan riddles, are relevant to remember.

In 1934, the Zen master Yamamoto Gempo defended the terrorists in his court testimony. "Yamamoto was so highly regarded by his fellow Zen masters that they chose him to head the entire Rinzai Zen sect in the years following Japan's defeat in August 1945" (source last linked).

In his revealing output, Brian Victoria has also emphasised an obscured reference found in the Suzuki article Rush Forward Without Hesitation (1941). This article appeared in Kaiko Kiji, the Imperial Army Officers Journal, in June 1941. Suzuki there states: "I believe one should pay special attention to the fact that Zen became united with the sword." This is a reference to soldier Zen. The wartime writings of Suzuki are a headache for his partisans, not to mention pacifists and Buddhist believers in ahimsa (non-violence). Suzuki praised medieval warlords like Uesugi Kenshin and Takeda Shingen for demonstrating the unity of Zen and the sword. These two sixteenth century samurai "were responsible for the deaths of thousands of their enemies and their own forces, each one of them attempting to conquer Japan. Suzuki lumps these warlords together as exemplars of what can be accomplished with the proper mental attitude acquired through Zen training" (Victoria, Zen as a Cult of Death).

Suzuki became ascendant in the 1930s with such works as Essays in Zen Buddhism. He had an influential habit of describing Indian Buddhism as inferior to the Japanese version. Suzuki expressed "a harsh view of the fate of Buddhism, particularly Chan, in China" (Jaffe 2014:xvi). He even stated: "There is no Zen in China worth speaking of" (ibid:xvii).

Less well known are Suzuki articles on the Nazi regime, appearing in a Kyoto newspaper of 1936. "When read in the context of the times, Suzuki's articles are actually a cleverly worded apologia for the Nazis" (Victoria, "D. T. Suzuki, Zen and the Nazis," The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 11 no. 4, 2013). The Zen exponent is disconcerting on the subject of Hitler's attitude to Jews. Brian Victoria here reminds that the content of these articles "reflected the pro-Nazi thinking of many Japanese at that time."

Like [Count] Durckheim, but unlike Herrigel, both Yasutani [Roshi] and Suzuki succeeded in leaving behind (or rather 'burying') their wartime pasts, presenting themselves to the Western world as the epitome of Eastern spirituality. (Victoria, A Zen Nazi in Wartime Japan, 2014)

This evocative reflection is significant. Karlfried Graf Durckheim (1896-1988) encountered Suzuki during a residence in Japan during WW2, when Durckheim was an agent for Nazi propaganda, while favouring comparison of German militarism with bushido. Durckheim was subsequently further confused by psychotherapists like Jung and Neumann; he even became regarded as a "Zen master." Eugen Herrigel (d.1955) wrote a book in German translated as Zen in the Art of Archery (1948; trans. 1953), associated with the Nazis. Herrigel joined the Nazi party in 1937, and was subsequently found guilty of collaboration with Nazism. Suzuki nevertheless praised Herrigel in a preface he wrote for the English edition of the latter's book. The lucid Brian Victoria comments: "Zen's connection to archery is primarily a postwar 'myth' that Herrigel himself promoted" (Victoria 2014, article linked above). See also Hans Joachim Bieber, Zen and War: A Commentary on Brian Victoria and Karl Baier's Analysis of D. T. Suzuki and Count Durckheim (2015).

.jpg)

Yasutani Haku'un Roshi

|

Yasutani Haku'un Roshi (1885-1973) was a Soto Zen priest who became a reputedly "enlightened master" in America after World War Two. Well known Western exponents of Zen promoted his sanitised teaching. However, Yasutani wrote a disconcerting wartime book (in Japanese) on the Soto Zen founder Dogen (d.1253). Zen Master Dogen and the Shushogi (Tokyo, 1943) was translated into German for the edification of Durckheim. That book contained the author's extremist right wing views. Yasutani, a committed imperialist, desired to save the people of Asia from America and Britain in the Japanese war project.

Victoria has revealed how, in his book of 1943, Yasutani expressed fervent nationalism, emphasised obedience to the Emperor, and castigated "demonic teachings of the Jews." The anti-Semitic component is pronounced. The Roshi here patriotically alleged that Dogen expressed reverence for the Japanese Emperor. Yasutani later travelled to the West several times during the 1960s, and was featured to advantage in Philip Kapleau, The Three Pillars of Zen (1969). This influential work made Yasutani famous. According to Victoria, the Roshi never acknowledged his wartime nationalist exposition. The relevant details came (for Western Zen enthusiasts) as "a jarring, visceral kick in the gut that forces a confrontation with such issues as the nature of enlightened mind" (The Hardest Koan, 1999).

In his 1943 nationalist outpouring, Yasutani Roshi wrote: "Of course one should kill, killing as many as possible. One should, fighting hard, kill every one in the enemy army." This was six years after the war horror known as Nanjing Massacre, when violent mass rape accompanied the high death toll created by Japanese soldiers in the Chinese capital. The details can shock sensitive readers to a substantial extent.

The cult of death subsequently lost popularity. "Yasutani's support of the Japanese military establishment was ignored, denied, or diminished; now, new research reveals Yasutani's rabid anti-Semitism at the height of World War Two if not before" (The Hardest Koan, article last linked)

Another Soto Zen priest, Masanaga Reiho, glorified the reckless young Kamikaze suicide pilots in 1945:

The source of the spirit of the Special Attack Forces [Kamikaze] lies in the denial of the individual self and the rebirth of the soul, which takes upon itself the burden of history. From ancient times Zen has described this conversion of mind as the achievement of complete enlightenment. (Victoria, Zen at War, p. 139)

Professor Victoria comments that this emphasis (shared by Durckheim) was tantamount to claiming that "typically teenage pilots" were fully enlightened. The nationalist bias here ignored pressure exerted on the pilots, from military commanders, to sacrifice their lives for the imperialist cause (Victoria 2014, article linked above).

The diaries of D. T. Suzuki reveal that he was in contact on forty-four occasions (between 1930 and 1945) with the military extremist Count Makino Nobuaki (ibid). This activist was a close adviser of the Emperoro Hirohito. Nobuaki (1861-1949), born to a samurai family, was an imperial court official who contributed to the militarisation of Japanese society. He influenced the Emperor into sanctioning the illegal invasion of China by the extremely violent Japanese army.

Suzuki urged that traditional Japanese Zen lacked social engagement and logic (ronri). He emphasised that logic was necessary for Westerners to accept Zen. The issue here becomes the extent to which he changed Zen from the older model via the "logical and irrational" format of Modern Zen, the extension of Meiji New Buddhism. Suzuki's version of Zen enlightenment was influenced by the thought of William James, and also by his close friend Nishida Kitaro (Jaffe 2014:xiii). Some critics say that Suzuki decontextualised Zen tradition. His version was nevertheless regarded as authoritative Zen by his Western supporters, who failed to discern the nationalist ideology at work. Suzuki Modern Zen should now be distinguished from the modern Rinzai and Soto monastic orthodoxies in Japan.

In 1984, there were over 23,000 ordained Zen priests in Japan. These men had undergone a minimum of two or three years monastic training. They staffed over 20,000 registered Zen temples in Japan. "The vast majority of these functioning Zen priests have little knowledge of, or interest in, the musings of intellectuals such as Suzuki, Nishida, or Hisamatsu" (Sharf, Japanese Nationalism).

Suzuki presented bushido to a Western audience as "the very embodiment of Zen" (Victoria, Zen as a Cult of Death). He glorified the sword in a well known work eventually entitled Zen and Japanese Culture, originating in the 1930s. This book conveyed the impression that samurai were Zen practitioners. Suzuki samurai ideation saturated the American Zen sector, where swords became revered as tokens of Buddhism. The samurai were a warrior class not basically inclined to contemplation or koan, although a number of them did opt for Zen affiliation, discernibly advantageous to Zen temples. New Buddhism apologists presented bushido as a code of chivalry. The operation of that martial code evaded fixed rules, serving relentless imperial purposes of conquest and colonisation. The samurai sword was an instrument of death and execution, with other savage excesses also occurring via use of that weapon.

The wartime writings of Suzuki on bushido were evidently regarded by the Japanese army as a boost for morale. His article Zen and Bushido was selected for inclusion in the "military-dominated" book Bushido no Shinzui (The Essence of Bushido). This was published in November 1941, less than a month before the Japanese air attack on Pearl Harbour. Other contributors to that work included the prominent Imperial Army General Sadao Araki (later sentenced as a class-A war criminal). The Prime Minister Fumimaro Konoe (1891-1945) penned the introduction. The Suzuki article stated: "When it comes time to act, the best thing is simply to act. You can decide later on whether it was right or wrong. This is where the life of Zen lies. The life of Zen must become just as it is, the life of the warrior" (Victoria, "The Negative Side of D. T. Suzuki's Relationship to War," The Eastern Buddhist 41, 2:97-138, pp. 134-5; article dated 2010). Critics say that this argument amounts to amoral relativism.

Brian Victoria informs that the same 1941 article by Suzuki "contained not so much as a single word acknowledging the immense suffering inflicted on the Chinese people by Japan's ongoing aggression" (ibid:136). This trait converged with the disposition of Prime Minister Konoe, who has the repute in earlier years of escalating the war with China after the Nanjing bloodbath; this aristocrat stated that Japan was irrevocably committed to conquest of China. Fumimaro committed suicide at the end of the Second World War, upon learning that he was to be tried as a suspected war criminal.

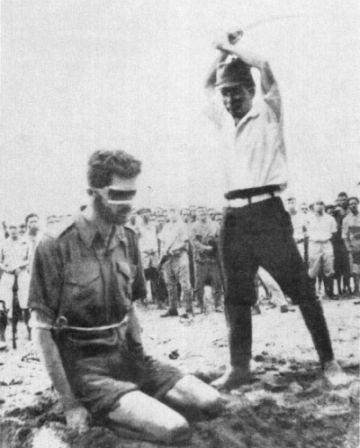

Between 1931 and 1945, the Japanese imperial army invaded and oppressed Manchuria, Mongolia, China, Burma, and elsewhere. Korea was already a victim of colonialism, and remained so for many years. The imperialist aggressor employed tactics of extreme violence (Edward Russell, The Knights of Bushido: A Short History of Japanese War Crimes, 1958). The neo-samurai army executed civilians, conducted massacres, wrecked cities, and abused prisoners. They launched a very brutal war against China, including the infamous Nanking Massacre of December 1937. The bloodstained swords and bayonets served imperial policies of conquest and devastation.

The Nanjing Massacre can still shock any sensitive person. At least 300,000 Chinese were killed, mostly civilians. At least 20,000 women were raped, while some estimates say 80,000. Most of the raped women were brutally killed by the "chivalrous" code of deadly bushido. Japanese soldiers (or samurai) raped girls less than ten years old, and women over seventy years old. They also raped pregnant women and nuns. Many women were gangraped by samurai terrorists. The molesters were also compulsive looters who burned Nanjing to ashes. "The brutalities included shooting, stabbing, cutting open the abdomen, excavating the heart, decapitation, drowning, burning, punching the body and the eyes with an awl, and even castration or punching through the vagina" (History of Nanking Massacre). Some victims were disembowelled. The Japanese government afterwards refused to apologise for these and other World War Two atrocities, though various statements of apology were subsequently made over the years.

The Japanese bayoneted infants, forced family members to rape one another, beheaded children, threw bodies into wells to poison the water supply, and buried civilians alive. It was the first of many similar massacres, though none took place on the same scale as that at Nanking. (Mel Judson, Japanese War Crimes)

Australian POW Sgt Leonard Siffleet being decapitated by a samurai sword at Papua New Guinea, 1943

|

The early 1940s saw the extension of bushido crime into horrific concentration camps of the Second World War. The samurai code of no surrender was matched by a contempt for prisoners still alive. When I was a boy, hideous stories about victims were fairly common in Britain. Unfortunately, many of these recitals were true and understated. My own mother informed me that a man in the same street as her family had become a concentration camp victim. He somehow managed to get a message despatched from bushido hell, informing his relatives in Cambridge that the abusers had cut out his tongue. My mother was allergic to the sight of Japanese swords, knowing that these weapons were used to execute prisoners. Some prisoners who returned alive to Britain could not adapt to ordinary life; these victims of torture and harassment had been pushed over a psychological precipice by their vicious tormentors. Many Second World War samurai swords, and earlier examples, eventually became popular as violence fetishes of a badly educated consumer population in Western countries.

One of the very numerous bushido atrocities occurred at Hong Kong in December 1941. The troops of General Ito Takeo arrived at a sanctuary for ninety-six wounded enemy soldiers. At the hospital entrance, the protesting medical doctor was shot in the head, his body afterwards being repeatedly bayoneted by compulsive murderers. "In the wards, a massacre of unprecedented ferocity took place. The Japanese ripped the bandages off the wounded patients and plunged their bayonets into the amputated arms and legs before finishing them off with a bullet" (George Duncan, Hong Kong Atrocities). Other bushido events occurred within the Hong Kong colony:

Atrocities were committed at various locations throughout the colony, including the rape of thousands of women and young girls. On this day, any misconceptions the world had that Japan was a civilised nation, disappeared into thin air. (Duncan, Hong Kong Atrocities)

The scale of samurai oppression extended to the so-called comfort women who were forced or tricked into living at Japanese military brothels between 1932-1945. The Japanese leaders destroyed many documents that might incriminate them; however, sufficient evidence remains as testimony to extensive abuse. Estimates of the number of victims have varied from 200,000 to 400,000. There were many Koreans, also Chinese and women of other nationalities, who became sex slaves of the samurai. These slaves were raped many times daily. They were also beaten (and even tortured). An unknown number committed suicide. Only about 25 percent of them are thought to have survived the ordeal. One of the Korean survivors eventually became famous as a protester. See Obituary: Kim Bok-dong (2019). Kim died at the age of 92, "without ever receiving the apology she wanted, still railing against the injustice."

The predatory samurai had no appreciation of any non-Japanese culture. Some of their victims were inmates of the Jingling Women's University at Nanking; students were taken away in trucks to live a degraded existence in Japanese army brothels. Despite all the evidence, Japanese nationalists still deny events they do not wish to remember.

From the invasion of China in 1937 until the end of World War Two, the Japanese military regime murdered nearly three million to over ten million victims. The death toll was probably about six million Chinese, Indonesians, Koreans, Filipinos, and Indochinese among others, including Western prisoners of war. The bushido democide was attended by a military belief that enemy soldiers who surrendered, while still able to fight, were criminals (R. J. Rummel, Statistics of Japanese Democide).

20.3 Hu Shih Version of Chan and Revisions

Coming from a very different background to D. T. Suzuki was Hu Shih (1891-1962), the Chinese philosopher and educator. He was not a subscriber to either Confucianism or Buddhism. His arranged marriage, in 1917, partnered him with an illiterate girl who suffered from the affliction of bound feet, a disability which had been encouraged by the Confucian system for many centuries. Meanwhile, in 1910, Hu Shih was sent to study agriculture at Cornell University in America. He moved on to Columbia University to study philosophy, there coming under the influence of his new tutor John Dewey (1859-1952), the famous pragmatist philosopher.

Hu Shih

|

Hu Shih returned to China after securing his doctorate. He became a Professor at Peking (Beijing) National University, the centre of intellectual life in China. He subsequently became a leading figure in the emergence of modern China. He served as the Republic of China's Ambassador to America (1938-42), and was also Chancellor of Peking University (1946-48). Afterwards living in New York, Hu Shih moved to Taiwan in 1958, becoming President of the Academia Sinica, a prominent scholarly organisation, founded in 1928 at Nanjing (subsequently at Taipei).

He was a prominent liberal intellectual in the May Fourth Movement of 1917-23. Hu Shih both advocated, and mediated, use of the vernacular as the official written language. The obstruction was the classical Confucian language which had been ascendant for many centuries. The masses were still ninety percent illiterate, blindly indoctrinated with Confucian tradition imposed by the higher classes. Hu Shih assisted a project of relegating the status of Confucian texts to that of reference works, as distinct from prescribed manuals to be routinely memorised.

Confucianism was now seen as a barrier to cultural growth, a religion advocating superfluous ritual, class distinctions, and a filial piety obstructing independent thought. Hu Shih was a strong critic of Confucianism. He also resisted nationalist sentiment, insisting that China must abandon "pretensions to uniqueness" (Hu Shih: An Appreciation). Until 1928, China was ruled by oppressive warlord regimes. Afterwards, as an independent intellectual, Hu Shih was in conflict with the Nationalist government. The subsequent Communist government was another doctrinaire problem for liberals. His output eventually reaped neglect and disdain, subsequently reassessed by Chinese scholarship in the late 1980s.

Hu Shih disagreed with the version of Zen Buddhism promoted by D. T. Suzuki. In China, Zen is known as Chan, which commenced long before the transplantation to Japan. According to Hu Shih, “Zen can be understood only within its historical context.” This statement comes from his 1953 article on Chan Buddhism in the journal Philosophy East and West. That article was entitled “Ch’an Buddhism in China: Its History and Method.” Hu Shih there states:

My greatest disappointment has been that, according to Suzuki and his disciples, Zen is illogical, irrational, and, therefore, beyond our intellectual understanding.... The Chan (Zen) movement is an integral part of the history of Chinese Buddhism, and the history of Chinese Buddhism is an integral part of the general history of Chinese thought. Chan can be properly understood only in its historical setting.... The main trouble with the "irrational" interpreters of Zen has been that they deliberately ignore this historical approach. "Zen," says Suzuki, "is above space-time relations, and naturally even above historical facts." Any man who takes this unhistorical and anti-historical position can never understand the Zen movement or the teaching of the great Zen masters. Nor can he hope to make Zen properly understood by the people of the East or the West.

In the same issue of the journal, featured the response of D. T. Suzuki, “Zen: A Reply to Hu Shih.” Suzuki did not retract his ideology. He maintained that Zen had to be understood within. The "irrational" Zen was generally triumphant outside China. "Hu Shih’s views were forgotten outside the ranks of scholarship, which has since tended to prove those views correct. In the uncritical sectors elsewhere, the influence of ahistorical Zen has been disastrous in various aspects of New Age belief and sentiment” (Shepherd, Some Philosophical Critiques and Appraisals, 2004, p. 107).

Hu Shih’s revised version of the Chan patriarch Shen-hui was very different to that of Suzuki, and is still of interest. He was the first scholar to study the Tun-huang manuscripts preserving the teachings of Shen-hui (684-758). His biographical study of that Chan practitioner was published in 1930. Hu Shih was partial to Shen-hui; however, his assessment of textual processes concluded that the traditional history of Zen amounted to “about ninety percent humbug and forgery” (quoted in Shepherd 2004:115). The pragmatic Hu Shih was nevertheless sympathetic in his conclusion that a sane method existed behind the apparent madness of classical Chan practitioners. There emerges an alternative complexion to such diverting Chan pleasantries as: “My dear fellow, how fine are the peach blossoms on yonder tree!” (quoted in Shepherd 2004:121, citing a 1931 article of Hu Shih).

According to Hu Shih, most Chan schools in the eighth century CE emphasised knowledge (prajna) instead of quiet sitting or meditation (dhyana). During the lengthy period 700-1100 CE, the Chan masters "taught and spoke in plain and unmistakeable language and did not resort to enigmatic words, gestures, or acts." This angle conveys a different complexion to the "irrational" question and answer method associated with koan, becoming standard in later centuries. According to Suzuki, the question and answer method amounted to prajna intuition. "The difference between Hu Shih and Suzuki is that between a historian and a religionist" (Wing-Tsit Chan, Hu Shih and Chinese Philosophy, 1956).

Assessments of the Hu Shih-Suzuki exchange have varied. A critical judgment comes from Professor John McRae, a more recent authority on Shen-hui, who says that “neither man [Hu Shih and Suzuki] seems to have had the interest or capacity to really consider the other’s position.” See John R. McRae, “Shen-hui and the teaching of Sudden Enlightenment in Early Chan Buddhism” (227-278) in Peter N. Gregory, ed., Sudden and Gradual: Approaches to Enlightenment in Chinese Thought (1987, Indian edn, Banarsidass, 1991), p. 261 note 15. The outlook of both contestants was quite clearly defined.

McRae has complained that Hu Shih interpreted the career of Shen-hui as a major transformation in Chinese intellectual and cultural history. “Hu defined this transformation as the reassertion of native Chinese values and the rejection of the Buddhist ideas that were so popular during the Six Dynasties and early T’ang dynasty periods” (McRae 1987:231). The basic fulcrum for this interpretation was the teaching of “sudden enlightenment” promoted by Shen-hui, a doctrine which Hu Shih viewed as being inherently Chinese in outlook. McRae urges that, although Chan Buddhism did undergo a major transformation in the latter half of the eighth century, this did not amount to a revolution in Chinese intellectual history. Further, Shen-hui was only one of a number of monks involved in this process of change, and the “sudden” teaching was only one of the doctrinal factors involved (McRae 1987:232).

Hu Shih referred, in his 1953 article, to the teaching of Shen-hui in terms of a “new Ch’an which renounces ch’an itself and is therefore no ch’an at all.” McRae juxtaposes this verdict with his own critical reflection that Shen-hui failed to give gradual cultivation any serious consideration, despite his concession to a period of such cultivation subsequent to insight or “awakening.” McRae assesses Shen-hui “as a missionary concerned only with increasing the size of the flock” (McRae 1987:254). Further, “the central thread that unites all of Shen-hui’s ideas and activities was his vocation of lecturing from the ordination platform” (ibid). The same scholar states: “Shen-hui’s polemical fervour correlates with doctrinal and practical superficiality” (ibid:251).

The image of a myopic Chan evangelist lends a critical context to attendant events celebrated in Chan lore. Shen-hui was the disciple of Hui-neng (638-713) and successfully campaigned for public recognition of this obscure monk as the sixth Chan patriarch. The famous Platform Sutra purports to preserve a sermon of Hui-neng. That document is now thought to have been composed circa 780 by a member of an early Chan grouping known as the Ox-head school. The teaching of the legendary Hui-neng apparently reaped oblivion. See Philip B. Yampolsky, The Platform Sutra of the Sixth Patriarch (1967). Shen-hui is now seen to have distorted the teaching of the so-called Northern School of Chan in his campaign against the “gradualists.” See McRae, The Northern School and the Formation of Early Chan Buddhism (1986). See also McRae, Seeing Through Zen: Encounter, Genealogy, and Transformation in Chinese Chan Buddhism (2003).

Complexities in the early situations of Chan are prodigious. Hu Shih tended to exalt Shen-hui. That zealous monk is now viewed by other scholars as an erring sectarian in the version of history he imposed. Shen-hui called his own tradition the Southern School, a term through means of which he annexed the East Mountain school associated with earlier Chan patriarchs. Whereas Hui-neng’s rival Shen-hsiu (d.706) was relegated to the status of the Northern School, purportedly possessing an inferior teaching of “gradual enlightenment.” The claim of "sudden enlightenment" merits due caution as an ideological innovation.

The Shen-hui depiction of “Northern School” has been questioned. That maligned contingent apparently considered themselves to be representatives of the “Southern School,” here meaning South India, from where the first Chan patriarch Bodhidharma supposedly originated. Zongmi (Tsung-mi), who claimed to be the fifth patriarch of Shen-hui’s ho-tze lineage, “was in many respects much closer to the Northern School than to his proclaimed master Shen-hui” (Bernard Faure, The Rhetoric of Immediacy, 1991, p. 13). For Zongmi, see 20.7 below.

Such considerations have prompted a sobering suggestion: “The demarcation line drawn by historians between the two schools may be purely fictitious or at least unstable” (Faure 1991:13). See also Faure, The Will to Orthodoxy: A Critical Genealogy of Northern Chan Buddhism (1997). See also Heinrich Dumoulin, Zen Buddhism: A History: Vol. 1: India and China (1988), p. xx, for the relevant observation: “The abundant historiographical literature that has emerged during the past two decades shows that Suzuki’s thesis on the ahistoricity of Zen has not really been accepted.”

The idea of a non-ritualist Zen, favoured in the West, is contradicted by relegated history. "Classical Zen ranks among the most ritualistic forms of Buddhist monasticism. Zen 'enlightenment,' far from being a transcultural and transhistorical subjective experience, is constituted in elaborately choreographed and eminently public ritual performances. The genre, far from serving as a means to obviate reason, is a highly sophisticated form of scriptural exegesis" (Sharf, The Zen of Japanese Nationalism).

See also Chih-P'ing Chou, English Writings of Hu Shih: Chinese Philosophy and Intellectual History Vol. 2 (Berlin 2013); Lou Yulie, "On Hu Shih's Study of Chan History" (66-86) in Yulie, ed., Buddhism: Religious Studies in Contemporary China Collection Vol. 5 (Leiden 2015).

20.4 Sudden and Gradual in Chinese Buddhism

Tang Dynasty Buddhist statues at Fengxian temple, Longmen Caves, Henan Province. Courtesy Wikipedia. The limestone seated image of Vairocana Buddha is 17 metres (56 feet) high, dating to 673-75 CE.

|

Chinese Buddhism involved the interplay and competition between several different Buddhist sects. These were eventually overshadowed by the Neo-Confucian philosophers who are thought to have assimilated some elements of Buddhism, however indirectly. Even within the phenomenon of Chan (Zen) Buddhism, rival sects produced different interpretations of basic meditation features deriving from Indian models.

The theme of “sudden versus gradual” can be found in various books on Zen. The relevant terms relating to sudden/gradual polarity have been closely analysed by specialist scholars, along with the textual locations. The sudden-gradual controversy is first attested in the debate visible between the Chinese Buddhists Tao-sheng (c.360-434) and Hui-kuan (363-443). The former promoted the theme of sudden enlightenment (tun-wu), whereas the latter defended gradual enlightenment (chien-wu). This was a pre-Chan occurrence. Tao-sheng has been credited with a Neo-Taoist tendency apparently influencing his “sudden” theme. Tao-sheng referred to gradual practice as a preparation for sudden enlightenment. See Whalen Lai, “Tao-sheng’s Theory of Sudden Enlightenment Re-examined” (169-200) in Peter N. Gregory, ed., Sudden and Gradual: Approaches to Enlightenment in Chinese Thought (Indian edn, Banarsidass 1991).

Gradualist teaching was an outcome of a basic Mahayanist position, being associated with the Indian character of early Mahayana. The Chan priest Shen-hui (684-758) denounced the gradualism (or meditation practice) of the “Northern” Chan school, associated with court circles at Laoyang. A uniquely Chinese version of Chan was traditionally believed to have resulted from the protest. The word ch’an basically means practice, being derived from the Sanskrit term dhyana (meditation). Shen-hui is traditionally associated with the figure of Hui-neng, the "Sixth Patriarch" of Chan and the subject of enthusiast lore created by later generations. See Philip B. Yampolsky, "The Birth of a Patriarch: The Biography of Hui-neng" (1714-52) in P. W. Kroll, ed., Critical Readings on Tang China Vol. 4 (Leiden 2018).

Hui-neng is described as an illiterate manual labourer gaining the role of sixth Chinese Chan lineage holder. The teachings attributed to him were elevated as the Platform Sutra, the word sutra being customarily reserved for teachings of Buddha (Peter Hershock, "Chan Buddhism," Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy). Much "Buddha Word" did not actually derive from the Buddha, but from the ingenious compilers of Mahayana texts.

The supposedly iconoclastic Chan of the “Southern” School was later presented in laconic format, contrasting with the more didactic and logical idioms of the Indian original. This trend provided “a new rhetoric with which to express sinitic Buddhist concepts.” The tangent is particularly associated with the Hongzhou school, reputedly employing tactics of beating, kicking, and shouting. Mazu Daoyi (709-788) was believed to have kicked a colleague in the chest. In a converging direction, Linji Yixuan (d.866) became renowned for employing a loud shout (ho) in his teaching method. See Robert E. Buswell Jr, “The ‘Short-cut’ Approach of K’an-hua Meditation” (321-377) in Gregory, Sudden and Gradual.

The “sudden” method of Linji was celebrated in verbal idioms such as: “Attainment is attained instantly, with no time required, no practice, no realising” (Buswell 1991:342). More recently, that form of exegesis became popular in America. A variant of this theme reads: “All persons are in fact already enlightened, and only mistakenly believe that they are not; hence, enlightenment involves nothing more than simply accepting that fact” (ibid). Shakyamuni and the many Indian generations of Buddhist monks would not have recognised this doctrine. Enlightenment here becomes meaningless.

The conventional assumption of continuity between Hui-neng or Shen-hui, and figures like Mazu, is contradicted by recent scholarship. Shen-hui locates to the era of “early Chan,” whereas Mazu belongs to the so-called “classical Chan.” The latter phenomenon is represented in the annals by “encounter dialogue,” meaning the spontaneous interaction between Chan masters and their students. The classical Chan dialogue exhibits paradoxes and conundrums. Related and very influential koan formulae were innovated by later Chan formulators of the Song era.

Discourses attributed to Mazu and his major disciples, and encounter stories about them, remained the lore of traditional Chan literature and were repeatedly read, performed, interpreted, and eulogised. Their images were idolised as representatives of Chan spirit and identity, not only by the successors of Chinese Chan but also of Korean Son, Japanese Zen, and Vietnamese Thien. (Jinhua Jia, The Hongzhou School of Chan Buddhism, State University of New York Press, 2006, p. 3)

Much of the subsequent Chan literature was retrospective, a creation of monks living centuries later. "Despite the iconoclastic image depicted by his successors of the late Tang to early Song, Mazu was well versed in Buddhist scriptures" (ibid:6). For instance, Mazu claimed Bodhidharma's transmission of the Lankavatara Sutra, a text rejected by Shen-hui. "Daily Life in Chan communities followed standard Chinese monastic precedents" (Hershock, last article linked, accessed 05/08/2021).

Encounter dialogues cannot be traced back to the Tang era. "Radicalised images" of Mazu and other Chan teachers first appear in the mid-tenth century record, well over a century after their deaths. The iconoclastic stories only became normative during the Song era. This process of invention permitted novel religious formulations to gain acceptance, facilitating the legitimisation of Chan (Poceski 2007:11). The Hongzhou school, created by the Mazu circle, is now credited with the establishment of a nationwide Chan orthodoxy that eclipsed earlier Chan traditions.

There were Chan reactions to “sudden” tactics. Criticisms of the Hongzhou tradition (or lineage) were notably expressed by Guifeng Zongmi (780-841), a very literate monk who complained that the mood of spontaneity was “often misinterpreted by ignorant students as advocating antinomianism” (Buswell 1991:336). Zongmi was a distinctive Chan historian, a Confucian convert to Buddhism associated with the Southern School. He relates how Shen-hui became elevated as the seventh Chan patriarch by an imperial commission in 796. Shen-hui’s attack on the Northern School evidently inaugurated “a period of intense and often bitter sectarian rivalry among the proponents of the different Chan lineages.” See Peter N. Gregory, “Sudden Enlightenment Followed by Gradual Cultivation: Tsung-mi’s Analysis of Mind” (279-320) in Gregory, ed., Sudden and Gradual, p. 280.

The Chinese Mahayanist schools of Hua-yen and T’ien-t’ai were at strong variance with Chan. The former two schools identified with the gradualism of the Indian heritage, and disapproved of the extremist Chan tendencies. Zongmi was so perturbed, at the rivalries dividing Chinese Buddhists, that he described the situation in terms of: “Buddhist teachings had become a disease that often impaired the progress of the very people they purported to help” (ibid). Seeking to offset this problem, he composed the Chan Prolegomenon. His purpose was to reconcile Chan with the scholastic traditions of Buddhist learning known as chiao. The latter represented gradualism.

The approach of Zongmi contrasted with the polemical attack of Shen-hui against the Northern School. The former was not only affiliated to Chan, but also to the Hua-yen tradition of Chinese Buddhism. His reconciling tactic stressed that he had encountered many Buddhists who used the terms “sudden” (tun) and “gradual” (chien) in a thoroughly inadequate manner. He enumerated the different ways in which the pervasive and confusing terms had been employed with regard to practice and enlightenment. The output of Zongmi is now viewed as a basically accurate account of Chan trends, providing a corrective to the later ideological landscape created by Song monks of Chan affiliation.

Zongmi explicated his own viewpoint in terms of “sudden enlightenment followed by gradual cultivation.” The Chinese phrase is rendered tun-wu chien-hsiu. In this charting, tun-wu is the actual foundation for practice via the initial insight (chieh-wu). That "sudden" insight is only the first stage in a tenfold process of spiritual cultivation said to climax in the complete realisation of Buddhahood. Some commentators have deemed this a form of gradualism, while others say that Zongmi straddles both sides of the “sudden-gradual” dichotomy. However, there are anomalies in relation to the standpoint of Shen-hui, whom Zongmi claims to represent in his own doctrine of “sudden followed by gradual.” This teaching was a conservative line of defence on the part of Shen-hui in some arguments, whereas the more radical teaching of “sudden enlightenment and sudden cultivation” (tun-wu tun-hsiu) was apparently the preferred doctrine of Shen-hui when he was on the offensive (Gregory 1991:305-7). See also Peter Gregory, Tsung-mi and the Sinification of Chinese Buddhism (1991).

Such considerations do, at the least, serve to guard against the more fluent and uncritical versions of Chan (Zen) which have been strongly influential outside China. Exactly who gained insight or enlightenment, or exactly who was most assiduous in spiritual cultivation, are questions that may be strongly pressed in the face of routine assumptions.

Despite advances in recent scholarship, "the overall picture remains fragmentary" concerning Chan during the Tang Dynasty (618-907). "It is precisely the elusive and changing nature of Chan Buddhism which leads to the difficulty in answering the question what Chan was" (Pei-Ying Lin, Precepts and Lineage in Chan Tradition: Cross Cultural Perspectives in Ninth Century East Asia (doctoral dissertation 2011, pp. 247-8, available online).

A relevant observation concerns Zongmi: "On the one hand he began to integrate ten diverse Chan schools into one grand narrative, and on the other hand he was strongly in favour of an integration of scholasticism and meditation" (ibid:247). A strong tension existed between scholarly monks in the capital and mendicant monks in the mountain regions. "For mendicant monks, the path to enlightenment relies on practices, namely meditation and the practice of bodhisattva-hood, rather than preaching to emperors and aristocrats" (ibid:250). The different approaches were not always opposed. "Contrary to the common understanding of Chan Buddhism, the Chan patriarchs were supposed to back up the authority of scriptures" (ibid).

The influential monk Shen-hui attacked the Lankavatara Sutra, with consequences of omission in Chinese Chan sources. That Indian text, together with the Indian patriarch Bodhidharma, comprised "the essential elements of the early Chan lineages" (ibid). Early Chan strongly related to an Indian monastic model of learning, whereas later Chan moved at a tangent.

Throughout the Tang Dynasty, Chan masters reputedly referred to "formless practice." Chan tradition nevertheless continued to insist upon repentance rituals and ordination ceremonies (ibid:81-82). Such discrepant factors were not elucidated in the popular contracted version of "Zen Buddhism" that gained favour in America during the 1960s, with distorting consequences.

Eventually, a severe persecution of Chinese Buddhism was launched by the rival Confucian hierarchy. "A new and virulent form of Confucian nationalism arose, viewing Buddhism as anti-Chinese, an economic parasite" (Welter 2006:8). The dateline here was 841-5 CE. The Buddhist clergy owned large landed estates. Over 250,000 monks and nuns were forced to resume a lay lifestyle. Over 5,000 Buddhist temples, monasteries, and libraries were destroyed by Confucian officialdom.

Contemporary with this misfortune was Linji Yixuan, a legendary figure later depicted as an iconoclastic Chan teacher. He is described in terms of "dismissing the great Buddhist scriptures as 'hitching posts for donkeys' and encouraging anyone who happened to see 'the Buddha' on the road to kill him" (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, accessed 05/08/2021). The tradition of Linji was one of the rural schools that flourished, while urban Buddhist trends were devastated by the Confucian reaction. Linji was not the "founder" of the Linji tradition, an assumption made by later generations, similar to influential beliefs in Bodhidharma as the founder of Chinese Chan and Hui-neng as the founder of the Southern School (Mario Poceski, Ordinary Mind as the Way: The Hongzhou School and the Growth of Chan Buddhism (Oxford University Press, 2007, p. 16 note 2).

The romanticised image of the Hongzhou school as an iconoclastic tradition expressed in later Chan texts - and widely reproduced in popular and scholarly works on Chan/Zen - is at odds with the historical realities of Tang Chan. (Poceski 2007:4)

The falsifying lore of Chan misconstrued factual developments. Mazu and his assocates were not outrageous radicals. Instead, they taught a Buddhist way appealing to officials and literati. Numerous disciples of Mazu belonged to the establishment of Chan priests. The early schools of Chan disappeared, replaced by an orthodoxy featuring followers of Mazu in the early ninth century. The Linji tradition is closely associated with the Mazu influence.

Numerous disciples of Mazu secured prominent clerical positions throughout China, including the two capitals. They attracted scores of disciples, some coming from as far away as Korea, and received support and approbation from famous literati, powerful officials, and the imperial court. Many of them were well educated and from gentry families. (Poceski 2007:5).

Chan gained a prestige role during the Song dynasty (960-1279), acquiring both religious and political standing. The majority of public monasteries supported by the Song court were Chan. "Members of the Linji faction headed influential state-supported monasteries and authored works commissioned by imperial edict" (Albert Welter, Textual History of the Linji lu). The Linji tradition also achieved influence in Korea and Japan.

Two and a half centuries after the death of Linji Yixuan, the Linji lu claimed to record his activities, dialogues, and sermons. There is more historicity attaching to the figure of his monastic contemporary Zongmi, whose Chan Prolegomenon is described as a sophisticated Indian style exegesis launched as a critique of competing Chan teachings. Zongmi urged that a transmitter of Chan must use Sutras and other works as a standard. In contrast, from the Edo period (1603-1867) onwards, Japanese Rinzai Zen marginalised the Sutra-based Chan of Zongmi and the later exponent Yongming Yanshou (d.976), author of Mind Mirror. The enigmatic koan format was instead preferred. The popular Western promotion of Chan and Zen (associated with Alan Watts and others) was strongly influenced by the Japanese sectarian preference to interpret Chan as eschewing words and language (Jeffrey L. Broughton, Zongmi on Chan, Columbia University Press, 2009).

Zen apologists of the twentieth century depicted Zen as a transcendental tradition remote from political connections and "above historical facts." Scholars like Albert Welter have shown that this interpretation is pronouncedly erroneous. The strong relation between Chan monks and political rulers was crucial to the success of Chan in China. During the Song era, the emerging Chan written record was influenced by considerations of court favour and literati patronage. See Welter, Monks, Rulers, and Literati: The Political Ascendancy of Chan Buddhism (Oxford University Press, 2006).

Chan masters of the Song era were appointed to prestigious monasteries, being supported by rulers and officials, while gaining honorific titles confirming their status. Chan doctrine claimed a unique approach to Buddhism, simultaneously winning patronage from the wealthy, as did other Buddhist traditions.

Chan transmission records, the literary collections documenting the Chan movement and its aspirations, were forged to champion certain Chan factions and their political supporters.... Local patrons erected new monasteries and designated which Chan masters would serve at major Buddhist establishments in their domains. (Welter 2006:6,11)

A new class of "scholar-officials" were patrons of the "new" Buddhism in the Song era. Chan was very much a part of this trend, being keen to dissociate from the aristocratic Buddhism of the Tang period. The objective was now to develop a new literary style with public appeal (ibid:14). This process culminated in the Chan literary forms of gongan and yulu (recorded sayings). Gongan is the Chinese equivalent of Japanese koan, being adapted from encounter dialogue. In subsequent centuries, koan was used extensively in Japanese Zen, and believed to facilitate enlightenment. Meanwhile, the Chan exegetes of Song China were preoccupied with the construction of lineages, meaning the master-disciple transmission featuring as a prominent component of doctrine.

In traditional Chan history, the rejected "Northern School" was viewed as being unworthy of serious consideration. Nevertheless, that school continued to exert a strong influence. Acknowledgment occurred in the Jiu Tangshu, a history of the Tang era compiled in 945 CE. The compilers here regarded the priest monk Shenxiu as the Sixth Patriarch of Chan, making no reference to the dissident Shen-hui (Welter 2006:32). The otherwise obscured figure of Yuquan Shenxiu (d.706) was much later resurrected by modern scholarship. This monk inherited a preference for the Lankavatara Sutra from his teacher Hongren (Hung-jen) at East Mountain. His last years were spent at the court of Laoyang, then one of the biggest cities in the world.

When Shenxiu left the East Mountain community, he withdrew into solitude. He may have reverted to a lay lifestyle. If so, he returned to monastic life at the Yu-chuan temple in Hubei province. He built a hermitage, located over a mile away from the temple, evidently desiring further solitude. Ten years later, he began accepting students. Shenxiu was invited to the court at Laoyang in 700 CE, when he had reached a ripe old age. He stayed at the court reluctantly, wishing to return home to the temple. He and his followers recommended both the sudden and gradual approaches, in accordance with personal ability and prior experience (Damien Keown, "Shen-hsiu," Oxford Dictionary of Buddhism, 2004).

Many years after the death of Shenxiu, in 732 his former disciple Shen-hui denounced him for abandoning the true teachings of Chan in a "gradualist" stance. The priest monk Shen-hui, existing outside court circles, accused his contemporary Pu-chi of usurping the title of Seventh Patriarch, and for having elevated his own teacher Shenxiu (Shen-hsiu) as the Sixth Patriarch. At this period, Chan compilers elaborated "a theory of the succession of Six Patriarchs, from Bodhidharma through Shen-hsiu" (Yampolsky 2018:1714). The earliest Patriarchs are regarded in terms of a legendary casting by some rigorous modern analysts.

Recovering the history of Chan (and other Buddhist traditions) is a pursuit hindered by sectarian preferences, canonical literature, retrospective doctrine, and substitute events. The same drawback applies to other religious traditions achieving a doctrinaire standpoint.

20.5 Shakyamuni Buddha and Early Indian Buddhism

For many years, Hinayana Buddhism has been less popular than other developments. Hinayana is the so-called Lesser Vehicle, in contradistinction to the Mahayana (Greater Vehicle). The word Hinayana was a stigma employed by later Mahayana exponents, denoting a supposed inferiority. "No Buddhist groups ever referred to

themselves as Hinayanists" (Hirakawa Akira, A History of Indian Buddhism, University of Hawaii Press, 1990, p. 256). The depreciatory term survived in modern coverages.

Hinayana represents the early Buddhism, a religion split into numerous offshoots developing from the original or “primitive” Buddhism. The search for Shakyamuni (Gautama) Buddha is a pressing matter. Only one of the "Hinayana" sects survived into later centuries, namely the Theravada, associated in some minds with a gloomy monasticism far inferior to the paradoxes of Zen (also a monastic tradition, despite the Western enthusiast attempt to modify and eliminate context). The resuscitation of Shakyamuni is not to be underestimated. Buddhism began in a North Indian habitat obscured by legend, textual intricacies, and sectarian rivalries.

The chronology of Siddhartha Gautama, alias Shakyamuni Buddha, has been disputed, some scholars favouring a date of 480 BC for his birth. However, other dates favoured for his birth are 623 BC and c.563 BC. He lived to be eighty years old. Archaeology has recently urged the sixth century BC as a relevant timeline. Excavation at Lumbini, in Nepal, the reputed birthplace, revealed a previously unknown timber shrine. Burnt charcoal in the postholes provided a radiocarbon dating (Oldest Buddhist Shrine Uncovered, 2013). There are disagreements about exactly what has been discovered.

Gautama was but one of several shramana sages who were in conflict with orthodox Brahmanism of the early post-Vedic era. Along with Mahavira (the Jain), he may be considered the most distinctive of these “forest philosophers,” to employ a generalising description. "To write about the life of Shakyamuni is a desperately difficult task" (Etienne Lamotte, History of Indian Buddhism, Paris 1988, p. 15). He was born into the Gautama clan of the Shakya tribe, identified with the border of India and Nepal. There are problems in extricating a biography from the Pali and Sanskrit sources. We may believe that this kshatriya adopted a mendicant lifestyle at the age of twenty-nine. After travelling from the Himalayas to Rajagriha, the capital of Magadha, he became a disciple of two Yoga masters, Alara Kalama and Udraka Ramaputra. Under their direction, he experienced a form of ecstasy. However, when he emerged from this samadhi, he found that his state was exactly the same as before. No transformation had occurred.

The mendicant thereafter desisted, moving to Uruvilva, where he undertook austerities for several years. Maintaining severe fasts and stopping his breathing, again he was disappointed. He accordingly "renounced such penances" (ibid:16). His ascetic companions then left him in disapproval, moving on to Varanasi. Gautama thereafter reputedly attained enlightenment at Bodhgaya, thus being freed from the cycle of rebirth.

.jpg)

Buddhist settlements in India. Courtesy Anil K. Pokharia, Researchgate

|

Shakyamuni (Gautama) gained monastic and lay adherents, a number of them brahmans. The early canonical works of Theravada Buddhism contain diverse references to his career. The events most celebrated are his miraculous birth in the Lumbini Garden near Kapilavastu, his enlightenment (bodhi) under a tree at Bodhgaya (in Bihar), his preaching the first sermon at the deer park near Varanasi (Benares), and his decease at Kushinagar. Later Buddhist tradition elaborated a hagiography several centuries after the death of Shakyamuni. He inspired a monastic order of a very disciplined type. A detailed monastic code (vinaya) emerged in the early Buddhist religion.

After ceasing extremist ascetic practices, Shakyamuni advocated a monastic "middle way" between householder indulgence and ascetic denial. Active in what is now Uttar Pradesh and Bihar, he apparently maintained a distance from Varanasi, "a centre of the Vedic sacrificial cults, which were in the hands of a professional guild of Brahmins, as well as of the cremation business - a city in which a heavenly after-life was offered for sale.... The majority of the Benares citizens, therefore, were cold and unfriendly towards the wandering mendicants who camped outside the city in such alarming numbers, and preached heretical ideas" (Hans W. Schumann, The Historical Buddha, Penguin 1989, p. 74). However, the mercantile classes, also the aristocracy, are strongly implied as supporters of Shakyamuni in his struggle with the priesthood (B. G. Gokhale, New Light on Early Buddhism, Bombay 1994, pp. 53-4).

The shramana Gautama was in strong opposition to Vedic religion. He considered ritual ablutions and fire sacrifices to be useless. He rejected animal sacrifices, occurring on a large scale amongst the high caste priests. "To the Vedic cult he opposed his view that all cults could be dispensed with" (Schumann 1989:75).

Shakyamuni accepted the law of karma (Pali: kamma), which “operates mechanically and incorruptibly to ensure that each one receives the appropriate fruits of keeping or breaking the rules” (ibid:147). He also accepted the reality of samsara, meaning the cycle of death and rebirth, or reincarnation, a process governed by karma. Life in samsara is determined by good or bad actions and incentives. Liberation from samsara is the objective. Notably, “the Buddha rejected ritual and cult observances; he considered that they only tended to attach us more firmly to samsara” (ibid).

The appropriate Sanskrit term for liberation is nirvana (nibbana). Nirvana is outside samsara, though not amounting to an Absolute (Shakyamuni did not teach that nirvana is samsara, a contradictory equation formulated centuries later). Negotiating the Vedic ritual society, he disconcerted Hindus by disavowing the doctrine of atman. Instead, he taught anatman, non-self. Shakyamuni denied being a nihilist. “Since the so-called person is only a bundle of phenomena with no ‘self’, and since its existence is inevitably bound up with suffering, its ending is no loss” (ibid:150).

The mendicant Shakyamuni taught the “noble eightfold path,” including right mindfulness. This was evidently not an unyielding dogma, because “in addressing the laity he often started from the questioner’s occupation, explaining the rules in relation to his means of livelihood and social status (ibid:148). "In the early discourses, the caste system remains the second most criticised theory, next to the doctrine of atman. Not only did the Buddha provide innumerable arguments against this conception of caste, he also practiced what he preached" (David J. Kalupahana, A History of Buddhist Philosophy, University of Hawaii Press, 1992, p. 27).

The Buddhist monastic community was known in Sanskrit as sangha. A basic difference existed between lay followers and the monks. “The rules or precepts of the sangha, of which there were approximately 250 for monks, were called the vinaya” (Akira 1990:63). Discipline was strict; if any of the most serious precepts were broken, then permanent expulsion from the sangha was the consequence. Temporary suspension could result from the violation of other precepts.

Women gained a significant role as nuns in this renunciate community. "Buddhism was the first religious tradition to recognise women's ability to attain the highest spiritual status attainable by any man" (Kalupahana 1992:27). Cf. Jainist details of considerable interest: "The Kalpasutra [an early Jain scripture] is quite clear that on Mahavira's death the tirtha which he had founded contained a body of female ascetics two and a half times as large as the number of male ascetics and a lay community containing twice as many laywomen as laymen, while it is also stated that during the fordmaker's [i.e., Mahavira's] lifetime 1,400 women as opposed to 700 men achieved salvation" (Paul Dundas, The Jains, Routledge 1992, p. 49). The conclusion is inescapable that women played a substantial role in the formation of shramana communities at this early period.

The original Buddhist lifestyle is often stated to have been itinerant, with a break during the rainy season. An alternative view suggests that "most of the Buddha's preaching was done in urban centres, wherein he may have spent extensive periods of time even outside of the vassavasa [rains retreat] period" (Gokhale 1994:55). Available statistics reveal that the number of suttas (discourses) he delivered in urban centres is "overwhelmingly large" at 83 percent of the total. This leads to a conclusion that the rule of living in a fixed location only during the rainy season, even during the lifetime of Shakyamuni, "had assumed the nature of an ideal rather than a reflection of the reality" (ibid). When monasteries later developed along the itinerant routes, new forms of organisation and economic complexity arose, emerging during the Mahayana era which started about the time of Christ.