|

19. HINDUISM AND GURUS

What is your view of Hinduism? Are you for or against gurus?

19.1 The Rajneesh Diversion and Siddha Yoga

Until the late 1960s, there was a strong bias in Britain against Indian religion. A popular upsurge of interest occurred largely because the Maharishi Mahesh Yogi (1917-2008) temporarily converted the Beatles to his Transcendental Meditation. Hinduism then became very fashionable in the West, though not always well understood. Mantras were glibly promoted to a new consumer audience who neglected study of Indian philosophy.

A decade later, a strongly antinomian form of guruism occurred in the shape of Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh (1931-1990), whose ashram at Poona became notorious for extremist practices in which some people were injured. Rajneesh was then caught in a predicament resulting from his agitations and excesses. He emigrated to Oregon, where his following became reckless in the mid-1980s, demonstrating antisocial behaviour and terrorist tendencies that shocked America (Shepherd, Some Philosophical Critiques and Appraisals, pp. 58-74). According to Indian critics, Rajneesh (Chandra Mohan Jain) was not a real guru; rejecting his ancestral Jainism, he employed Western alternative therapy and sexual libertinism to seduce his gullible audience, who were largely Westerners.

The teaching of Rajneesh was explicitly permissive, contrary to the traditional discipline observed by many Indian gurus. Some other famous gurus also gained unfavourable reputations. Swami Muktananda (1908-1982) lost rating in the reports of his sexual abuse of devotees. The acquisition of wealth emerged as a danger symptom. More recently, the millionaire Sri Chinmoy (1931-2007) has been profiled as a deceptive and predatory guru.

Muktananda was introduced to the West, in 1970, by the eccentric LSD user Richard Alpert. His followers established over thirty centres for this guru. Muktananda taught Siddha Yoga, which became the name of an organisation, associated with ashrams in India and America. Soon after his death appeared The Secret Life of Swami Muktananda (1983), based on 25 interviews with members and ex-members of his community. This document revealed the sexual activity of the guru with female followers. A decade later came the expose of Siddha Yoga entitled O guru guru guru, appearing in The New Yorker (1994). Other reports can be found at Leaving Siddha Yoga.

A more recent contribution is Finding and Losing My Religion, composed by the psychoanalyst Daniel Shaw. This follower of Siddha Yoga at first disbelieved the reports that Muktananada was “relentless in sexually preying upon female followers, many of them girls who were not of legal age; when some followers exposed him publicly, he lied and attempted to cover up the scandal.” Threats of violence were directed at the critics. Shaw rejected Siddha Yoga in 1994, and later “came to learn of far more extensive sexual abuse of both young girls and adult women, several of whom I met and spoke with.” The reports were resisted by Muktananda’s successor Gurumayi Chidvilasananda. Shaw informs in the same article:

I had heard her [Gurumayi] tell blatant lies and had witnessed her deliberately, maliciously deceiving others she wished to embarrass or harass while she expressed pleasure in doing so. I witnessed her condoning and encouraging illegal and unethical business and labour practices, such as smuggling gold and US dollars in and out of India, and exploiting workers without providing adequate housing, food, health care, or social security. I was aware that, for many years, Gurumayi and her predecessor, Swami Muktananda, had been using spies, hidden cameras, and microphones to gather information about followers in the ashram, which they then used to embarrass them, often publicly. All of these behaviours were well known to those of us on the staff of the organisation, but they were much less familiar to the thousands of followers who did not live and work there in direct contact with Gurumayi. (Finding and Losing My Religion)

Gurus were not the only deficient parties. The traditional discipline of Hinduism was frequently overlooked by Western enthusiasts reared to a different lifestyle. Many hippies and neo-hippies adopted elements of Hindu teachings, making no serious attempt to be celibate, for instance. Yoga and Vedanta became a commercial exercise in the West, while the textual and historical complexities of Hinduism were almost exclusively an academic preserve, to which the popular manifestations of enthusiasm were indifferent. That discrepant situation continues today.

19.2 Swami Ghanananda

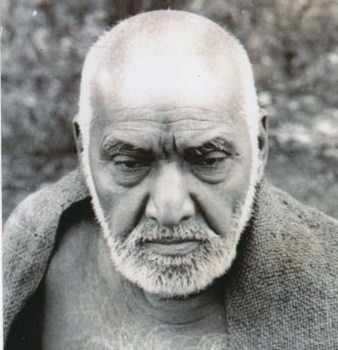

My own introduction to Hinduism occurred just before the wave of popular interest. I was able to witness some of the changes occurring in the reassessment of the late 1960s and early 70s. In 1967 I undertook a brief retreat at the Ramakrishna Vedanta Centre in London. The presiding figure was Swami Ghanananda (1898-1969), a senior monk of the Ramakrishna Order (more specifically, the Ramakrishna Math and Mission). He was very disciplined in his lifestyle. This did not prevent him from being communicative, and very humorous, at the communal mealtable.

A South Indian brahman, Ghanananda gained an academic degree at Madras University. He had known some of the last living disciples of Ramakrishna of Dakshineshwar, the figurehead of his monastic order. In India that monastic order was noted for attention to social work, plus the traditional contemplative routines. I was unable to find any fault with the example of Ghanananda. However, I did not choose to join the monastic order as he suggested. I wished to maintain a neutral attitude towards different religious movements.

Monks like Ghanananda did not receive any high profile publicity. This Swami was known only to a small local audience of supporters and Ramakrishna devotees in London. He died two years later, unknown to the media. Ghanananda lived in a simple room at a house in Muswell Hill that he had acquired for his Order. In acute contrast were television appearances of the Maharishi, making the dispenser of Transcendental Meditation (TM) a famous icon of flower power and a showbiz personality. The Beatles were attracted and then repelled. In later years, the Maharishi was reported to be charging very substantial fees, having gained super-rich followers who attended his meditation retreats. By the time of his death, the TM enterprise was stated to be worth more than three billion dollars. In contrast, the retreat I attended at Muswell Hill was free of charge, and solely a matter of personal study at one’s own convenience. There were only three retreatants, no media ads being involved.

19.3 Swami Vivekananda

Ghanananda sometimes complained that Westerners in general did not understand Hindu religion, and were at a loss to evaluate entities like Swami Vivekananda (1863-1902), who founded the Ramakrishna Order in the 1890s. An academic friend of mine, an enthusiast of Western philosophy, demonstrated the ethnocentric drawback. He caricatured Vivekananda for being too oratorical in some of his lectures, following a successful appearance at the Chicago Parliament of Religions in 1893. However, the critic did concede that Vivekananda had to compete with Christian missionaries in the late Victorian era, and furthermore, that his concern with social improvement and sense of affinity with the poor did set him apart from the Transcendental Meditation exemplar. The British critic had a degree in chemistry; he preferred Schopenhauer to Vedanta. His attitude was perhaps typical of British universities at that period, meaning the 1960s.

Swami Vivekananda

Swami Vivekananda is not fairly comparable to the later spate of Indian gurus who migrated to the West. Their laxities and commercial appetites contrast with Vivekananda’s preferred austerity, his many free lectures and classes, and his memorable anguish over the fate of his depressed countrymen who suffered under brahmanical stigma (and not just the British Empire opportunism). His opposition to priestly attitudes and phobias is notable. The high caste contingent criticised him for leaving the homeland of India, regarding him as an outcaste on the basis of this action. Vivekananda often ridiculed the orthodox attitudes. After spending a few years in the West, he returned to India, subsequently establishing the monastic organisation known as Ramakrishna Math, named after his teacher in Bengal. His approach to some aspects of conventional Hindu religion was radical, evidencing a reformist temperament. He lamented the plight of women and untouchables (Dalits).

Vivekananda elevated Advaita Vedanta to a pinnacle position in his ideology. However, he also extolled other dimensions of Hinduism. His last years were afflicted by ill-health; he died at the age of thirty-nine. His lectures, correspondence, and other output can be found in The Complete Works of Swami Vivekananda, a multi-volume collection having achieved successive editions. See also S. N. Dhar, A Comprehensive Biography of Swami Vivekananda (2 vols, 1975-6). Another atmospheric work is Reminiscences of Swami Vivekananda by his Eastern and Western Admirers (1961).

19.4 Maharishi Mahesh Yogi

The Maharishi Mahesh Yogi remained a problem to many critical onlookers. His Transcendental Meditation (TM) involved the repetitious chanting of mantras. Critics viewed this as a form of self-hypnosis, despite the enthusiastic reception by partisans. During the 1970s, the Maharishi innovated the TM-Sidhi programme, which promoted levitation. In 1978, he said on television that thousands of his students could levitate. Many claims were made for the benefits of Yogic Flying. Sceptics were very resistant.

Maharishi Mahesh Yogi

The notorious inclination of the Maharishi for commercial gains was another deterrent. His first world tour occurred in 1958, when he had only a modest following. Over the decades he gained many thousands of followers and nearly one thousand TM centres worldwide. His income was reported to be six million pounds a year. In Britain alone he purchased several mansions. In 1998 his property assets were valued at 3.5 billion dollars (FAIR news, April 2008, p. 14). By the time of his death in 2008, the charge for a five day session of TM was 2,500 dollars, while a three day induction course was promoted at £1,280.

In 1974, this guru founded the Maharishi International University (MIU), thereafter based at Fairfield, Iowa. One of his well known followers exited from this milieu in 1989, now realising that she had spent "over two decades in a dictatorial, repressive organisation, largely motivated by fear." Reference is made to the Maharishi's "manipulative fear and intimidation tactics." The inmates of MIU "lived in terror of banishment" (Susan Shumsky, Living in a Cult for 20 Years - Here's How I Broke Free, 2018, online).

19.5 Indology, Ramana Maharshi, and Neo-Advaita

The American enthusiasm for Eastern religions was very much stronger than the British counterpart, which tended to reflect the big brother. During the 1970s, the various fashions and trends in this sector of interest were often very unconvincing, and even ludicrous, to observers. The callow attitudes culminated in the Rajneesh debacle. Some gurus were making vast sums of money. Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh (alias Osho) acquired a large and superfluous fleet of Rolls Royce automobiles for which he invented an indulgent explanation to bemuse his followers (see article 24 on this site).

During the 1970s, I studied more Buddhism than Hinduism, subsequently rectifying the imbalance during the following decade at CUL (Cambridge University Library). Some of the results were included in Minds and Sociocultures Vol. One (1995), pp. 389-721, providing an overview of Vedism and Hinduism, using the works of Indologists like Jan Gonda.

Indology is not popular amongst many Western followers of sectarian Hinduism. Analysis of hard core matters extends to caste principles, rigorous examination of textual sources claimed as divine inspiration, and the formation process involved in sectarian organisation and doctrine. For instance, there are many texts attributed to the early medieval Advaita exponent Shankara. However, specialist scholars do not accept the authenticity of various Shankara texts.

When duly studied, Indian philosophy is a significant phenomenon, varying from the academic example of Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan to the origins of Buddhism and Jainism. The Vedantic texts known as Upanishads are another feature of interest.

Ramana Maharshi

Investigators of new age literature observed that the ashram of the deceased Ramana Maharshi (1879-1950) became incorporated on the “alternative” map of tourist activities. This development was accompanied by disconcerting trends of exegesis amongst some Western enthusiasts in relation to the Advaita teaching of Ramana, who lived in the Tamil country of South India. I first read about Ramana Maharshi when I was sixteen; the general situation was then very different. His lifestyle of basic simplicity did not involve any miracle stunts or insidious economic expansion (Some Philosophical Critiques and Appraisals, pp.153-158). He taught a version of Advaita Vedanta, a traditional doctrine of “non-dualism” which has provoked imitations and misunderstandings.

An early promoter of Ramana Maharshi was Paul Brunton, whose Hidden Teaching Beyond Yoga (1941) became popular in the West. Brunton was by that time banned from Ramanashram as a plagiarist; he ventured an ethical criticism of Ramana. Brunton's career is in dispute. His well known book A Search in Secret India (1934) is noted for a rejection of Meher Baba (1894-1969), the presentation being markedly distorted and misleading. Meher Baba is a figure mistakenly associated with Hinduism. He was actually of Irani Zoroastrian birth, his father being Sheriar Mundegar Irani. While Meher Baba did include Sanskrit vocabulary in his teaching, he was not a Vedantist. One of his teachers, Upasani Maharaj, was a Hindu, while another was a Muslim, meaning Hazrat Babajan of Poona. Like other religious movements, the Meher Baba movement has exhibited a tendency to suppression of unwanted materials.

The first Western guru to extensively misappropriate the Advaita doctrine was an American who sported the names of Da Free John and Adi Da Samraj (see article 14 above). His antinomian example did not resemble the restrained lifestyle of Ramana Maharshi and other Hindu Advaitins. There have been other Western claimants to the achievements associated with the Advaita doctrine, including Andrew Cohen. This trend, known as neo-Advaita, has strong tendencies to a commercial exposure. The macrocosm-microcosm doctrine associated with the Sanskrit words Brahman and atman is easily annexed, with no great philosophical acuity in many cases. The facile claim is evidently a problem in India also.

19.6 Atheistic Rationalism Versus Miracles

A radical trend of exegesis, emerging in India, is associated with atheistic rationalism. This manifested in a noteworthy campaign by Basava Premanand (1930-2009) to expose the deceits of holy men who claim “miracles” and supernormal feats. The large population of Hindu holy men comprise varying temperaments, ranging from retiring meditators to exhibitionists using crude forms of showmanship in full public view. The very deceptive “miracle” feats, such as swallowing fire and walking on burning coals, have gained alternative explanations. This is because atheistic Indian rationalists can perform the same feats, as they have demonstrated on the media.

The desire to appear spiritually advanced can exploit the credulity of an audience. The opposition of Premanand to Sathya Sai Baba involved a campaign to expose purported “miracles” relying upon sleight of hand and other deceptions. However, the miracle ruse is not the only basis for complaint in that direction (sexual abuse being a major objection). Ex-devotees of Sathya Sai like Robert Priddy complained at length about abuses. There are currently many audiences who need to be on their guard against gullible tendencies, lofty claims, and presumed holiness.

A drawback for generalising coverages is the proportion of those Hindu gurus and practitioners who do not rely upon “miracle” stunts in their projection. The “non-miracle” category have varied in their disposition, with eccentricities being visible here and there. Some of these entities may still exploit the appearance of holiness, especially where any form of media is in the offing.

19.7 Ramakrishna and the Homoerotic Theory

Ramakrishna of Dakshineswar

A controversy arose concerning Ramakrishna of Dakshineswar (1836-1886). This Bengali brahman was the inspirer of Vivekananda. Liiving at a Kali temple, his lifestyle was very simple; he did not gain any great fame during his lifetime. Being averse to money, Ramakrishna did not acquire wealth. He had no ashram or bank account. Though eccentric in certain of his habits, he was definitely not one of the miracle stunt holy men. Ramakrishna did not take classes or give lectures, and did not write any books. His teachings during his last years were recorded in a lengthy work known in English as The Gospel of Sri Ramakrishna, originally the Bengali Kathamrita of Mahendranath Gupta. The British novelist Aldous Huxley wrote an approving foreword to the 1944 English version translated by Swami Nikhilananda. A well known and more compact book by Christopher Isherwood is Ramakrishna and his Disciples (1965).

Three decades later, the very controversial Kali’s Child (1995; second edn, 1998) attempted to place Ramakrishna in a homoerotic perspective, inspired by neoFreudian beliefs and the “personal lens” of Professor Jeffrey J. Kripal. A number of Western assessors accepted this book at face value. In India (and elsewhere) there was strong resistance. The author was accused of possessing an inadequate knowledge of the Bengali language. Kripal apologised for his translation errors (many of which were corrected in the second edition). Kali’s Child militated against the Kathamrita and an early Bengali biography by Swami Saradananda. A critique from the Ramakrishna Order appeared in 2000. A total of 191 mistakes in the Kripal book were listed. The accusation was here made that Kripal had deliberately ignored evidence which contradicted his theory. See further the critical analysis in Swami Tyagananda and P. Vrajaprana, Interpreting Ramakrishna: Kali’s Child Revisited (Delhi, 2010). See also Views on Ramakrishna.

Critics say that Kripal committed further mistakes by writing (in 2003) an approving foreword to a disputed book by Adi Da Samraj. This notorious American guru really was oriented to erotic experiences (see article 14 on this site). Kripal expressed high praise of the Adi Da output, a factor which could spell the death of credibility for neoFreudian interpretations. The Kripal adventures in alternative thought subsequently endorsed the “anything goes” milieu of the Californian "human potential" centre known as Esalen. See Kripal, Esalen: America and the Religion of No Religion (2007). One could argue that the Esalen-Grof-Adi Da-Kripal synthesis is a sure recipe for social and psychological confusions.

19.8 Aurobindo and Esalen

The association of Aurobindo with the Esalen Institute at Big Sur occurred over a decade after the death of that Hindu sage. The Californian “integral” consumption of varied doctrines has not always led to any clarification or resolution satisfactory to observers elsewhere.

Aurobindo Ghose

Aurobindo Ghose (1872-1950) followed a much more traditional pattern than that associated with Daism. Innovating “integral yoga,” he was a prolific writer. Originally a militant nationalist in opposition to the British Raj, his subsequent jail sentence was accompanied by a change in outlook. In 1910, he found refuge at the French colony of Pondicherry and began to write books on Hindu religion.

His two most famous works are The Life Divine and The Synthesis of Yoga. See also the multi-volume Collected Works of Sri Aurobindo (1972). He retired into seclusion in 1926. A French female disciple gained salience from that time on by establishing his ashram, which he delegated to her supervision. The Shri Aurobindo Ashram only had some two dozen members at that time. The number is much higher today. Mira Richard (1878-1973) became an authority figure known as “the Mother.” In the 1960s, she established the colony of Auroville near the ashram at Pondicherry. Auroville is sometimes described as an international town.

The most well known book of Aurobindo is The Life Divine, a lengthy work on spiritual evolution which has a canonical status at Auroville. This book also became influential at Esalen, via the founder Michael Murphy. Some say that Esalen Aurobindo should be distinguished from the Indian original. The real Aurobindo had nothing to do with commercial “workshops” of new age innovation. However, he made an unfortunate prediction in The Life Divine about “a race of gnostic spiritual beings.” This concept tended to be popular in Esalen circles. The context sounds unrealistically utopian to critical analysts. By current standards, such a race would take thousands or even millions of years to develop. There are both exacting and casual definitions of the word gnostic, which currently means something like superclown in the jargon emanating from Esalen.

The Human Potential Movement, associated with Esalen, was a seedbed for imaginations and assumptions about spiritual advancement (see article 10 on this site). The action of such imaginations may be described as something very similar to falling off a log into the mire of narcissism. A commercial edge to the “workshop” programmes of Esalen cued recruits to excesses on record, including psychoactive drugs advocated by the high priest of Esalen, namely Stanislav Grof. There were other casualties involved, such as those sustained by the Findhorn Foundation Grof phase. The Esalen race of pseudo-gnostics and victims were so frequently assuming status as “self-realised,” “enlightened,” “integrated,” “empowered,” and many other variations on the same deceptive theme. Wisdom remains elusive, something not purchasable in "new spirituality" workshops, no matter how many thousands of dollars are extracted from the credulous.

19.9 Upasani Maharaj

Upasani Maharaj

A relatively obscure guru is Upasani Maharaj (1870-1941), also known as Upasani Baba. The spartan existence of this figure contrasts with a comfortable ambience preferred by many more recent Indian gurus of commercial orientation. Upasani wore sackcloth, not an ochre robe, nor an opulent gown in the Rajneesh style. He rejected miracles, and warned against those who exploited this subject.

His phase of discipleship, under Sai Baba at Shirdi, is frequently misrepresented. This drawback was a consequence of misunderstandings and sectarian fervour on the part of B. V. Narasimhaswami, a sannyasin from Madras who appeared on the scene many years later.

Living at the derelict Khandoba temple in Shirdi, Upasani became indifferent to the presence of scorpions and snakes. He departed for a time to other places, including Kharagpur in West Bengal, where he notably lived in a bhangi colony of Dalit sweepers and scavengers. When he returned to Shirdi, he was becoming famous, a factor of increasing concern to zealous devotees of Sai Baba. The facts were squashed and eliminated in well known devotee accounts.

At the village of Sakori, Upasani selected a local cremation ground as his home in 1918. At first, there was no accommodation for visitors. Subsequently, an ashram began to form. In 1922, he resorted to confinement in a bamboo cage. He remained completely unwesternised. He spoke Marathi and Sanskrit, but not English.

During the 1930s, he established at Sakori the Kanya Kumari Sthan. This distinctive community comprised kanyas or nuns, including Godavari Mataji (d.1990). The project was resisted by brahmanical orthodoxy, who customarily curtailed the activity of women and denied them the attainment of spirituality. Upasani Maharaj survived court cases against detractors, emerging as the victor.

|